- April 26, 2024

Product designers and machinists utilize different types of holes in manufacturing different modern products. Blind holes are commonly used for machining due to their extensive manufacturing benefits, including space utilization, enhanced product aesthetics, and strength. They are standard design features, indentations of varying shape and depth that do not lead to the opposite side of a workpiece.

This article will discuss blind holes in engineering and machining, their importance, and application. You’ll also learn about other types of holes in engineering and machining and helpful considerations for successful blind hole machining. Let’s get to it!

What is a Blind Hole in Engineering and Machining?

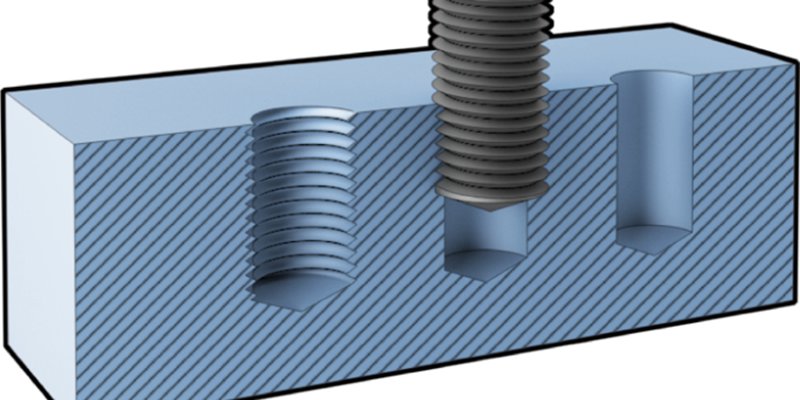

A blind or pocket hole is a cavity/hole that doesn’t lead to the opposite end of the workpiece material. This hole can be reamed, milled, or drilled to a specific depth without completely going through the material to the opposite side. Therefore, the hole is usually closed at the bottom, creating a recess for fasteners, screws, dowels, slots, and other components. The blind hole derived its name because it is impossible to see through it.

Machinists often use a blind hole in metal and woodworking projects to ensure the fit is tight enough to hold and conceal screws or parts for a unique appearance. Machining blind holes in workpieces also allows the creation of top-quality products with intricate features or shapes in industries requiring precision and enhanced strength.

Callout Symbol of a Blind Hole

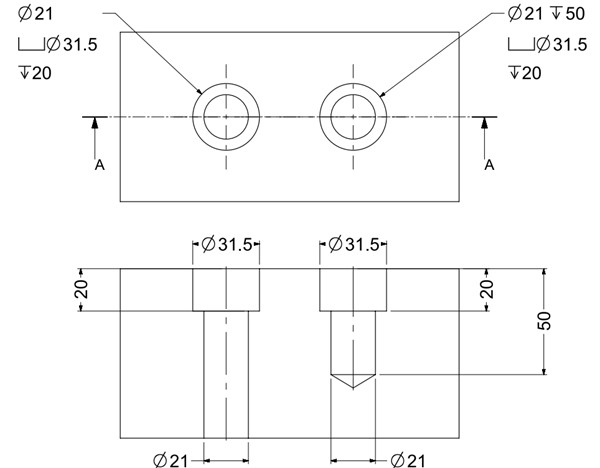

Product engineers and machinists often use standardized symbols to communicate design requirements in the manufacturing arena. The callout symbol of a blind hole shows its desired location, thread pitch, fastener size, diameter, and depth specification on the engineering drawing. Therefore, this callout symbol helps machinists and product engineers understand the design intent and accurate hole drilling.

How to Drill Blind Holes Step by Step

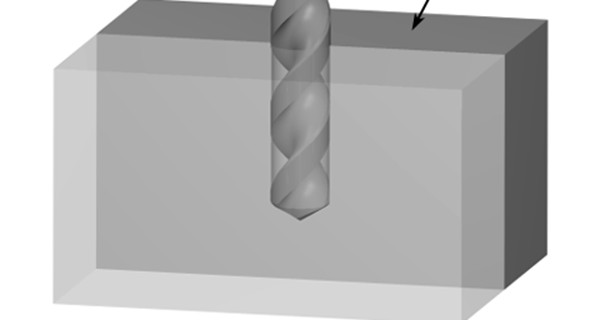

Drill holes in components require careful execution to achieve accurate depth and alignment. Below is a stepwise guide to drilling precise and accurate blind holes.

Prepare the Workpiece

First, you must firmly secure the workpiece with a vise or clamps. Ensuring the workpiece is positioned securely to prevent any deflection or movement during the process. Then, mark the hole’s center on the workpiece’s surface with a sharp pointed tool or a center punch. This creates a starting point for the drill bit and helps to keep it from deflecting.

Choose the Appropriate Drill Bit

Since there are different types of drill bits, the drill bit’s size must match the hole specifications you intend to drill. After choosing a suitable drill bit with the appropriate radius, insert it into the drill chuck and tighten it firmly. Also, ensure it is properly aligned to prevent deviations or wobbling during hole drilling.

Determine the Drilling Depth

Set the drilling depth and calculate the required distance between the drill bit’s tip and the desired blind hole end. Create a visual guide using a marker or a piece of tape to mark this depth on the drill bit, which serves as a depth indicator.

Begin Drilling and Monitor the Drilling Depth

Set the drill bit on the marked center point of the center hole. Then, moderate and constant downward pressure must be applied while maintaining a stable drilling speed. For easy and efficient blind hole machining, start by drilling the hole slowly to cut a pilot hole, then increase the speed gradually as the hole gets deeper.

While drilling, stop and examine the hole depth periodically using a depth gauge or a piece of tape attached to the drill bit.

Remove Debris

Debris may form in the hole as you drill since drilling generates chips. Hence, it is important to withdraw the drill bit occasionally to clear the debris. This helps prevent the chips or debris from hindering the precision of the drilled hole.

A drill flute or hand-operated air gun is commonly used for debris removal when drilling. You can use cleaning techniques like compressed air and a high-pressure stream of liquid coolant.

Complete and Inspect the Blind Hole

Drill the hole until you have attained the preferred depth as marked. You can employ different post-finishing processes to smooth the hole or achieve a fine finish.

In addition, once the blind hole has been drilled, inspect it to confirm that it meets the specified diameter and depth. Also, check for any rough edges or burrs that may require additional processing.

What are the Pros and Cons of Blind Holes?

Advantages of Blind Holes

Blind holes in engineering and machining offer extensive benefits in different applications. Here are some of the expected advantages of blind holes:

Improved Aesthetics

Blind holes improve the aesthetics of manufactured components by concealing fasteners, making them visually appealing without the visible protrusion of traditional fastening elements. This attribute is fundamental in industries where aesthetics is critical, such as consumer electronics and automotive.

Increase Strength and Reduce Stress Concentration

Machining blind holes in a component reinforces its strength by distributing weight evenly and improving the overall stability of the workpiece. Blind holes prevent potential failure points and ensure the extended product lifespan by reducing stress concentration.

Reduce Weight and Save Space

In applications like electronics or aerospace, where space is limited, blind holes allow products with more compact designs to be created. Hence, manufacturers can optimize available space and make sleek and lightweight products.

Limitations of Blind Holes

Blind holes have various limitations, even though they are helpful in various applications. Here are common setbacks of blind holes:

Potential Trapped Debris

Debris or chips can easily get trapped at the bottom of the blind holes since these holes don’t penetrate through to the other side of the material. More importantly, inspecting and cleaning the holes can be difficult since it is impossible to see all the way through blind holes.

Tapping Complexity

Challenges may occur when tapping a blind hole, which may be more complex than tapping through holes. It would not be easy to ensure the uniformity and accuracy of the threads in a blind-tapped hole.

Material Warping or Deformation

The integrity of material around a blind hole can be compromised when machining blind holes in materials like ABS, aluminum, and low-carbon steel, which are especially prone to deformation under heat or pressure.

Various Applications of Blind Holes

Blind holes are commonly used in various applications due to their increased strength and aesthetic benefits. Typical applications of blind holes include:

Aviation

Manufacturers in this field often use blind holes in constructing different aircraft components purposely to reduce weight without sacrificing the airplane part’s primary strength.

Electrical and Electronic Components

Engineers and machinists often use blind holes in electronic circuit boards to make mounting points for components like connectors, standoffs, and spacers. These holes facilitate secure attachment without damaging traces or components on the opposite end of the board.

Architecture

Blind holes serve aesthetic purposes in metalworking, woodworking, and other crafts. Manufacturers use these features to create visually appealing s=designs by filling them with contrasting materials like epoxy resin and metal inlays.

Mold and Die Making

Blind holes are used to produce mold and die for injection molding, forming, and casting techniques. They establish mounting points for cooling channels, ejector pins, and alignment features and help to improve mold performance and quality of molded parts.

Automotive

Automotive manufacturers employ blind holes in motor blocks and transmission parts for reliable attachments and to reduce material usage.

Considerations and Tips for Drilling Blind Holes

Blind hole machining requires attention to detail to attain desired outcomes. Here are some helpful considerations for effective blind hole drilling.

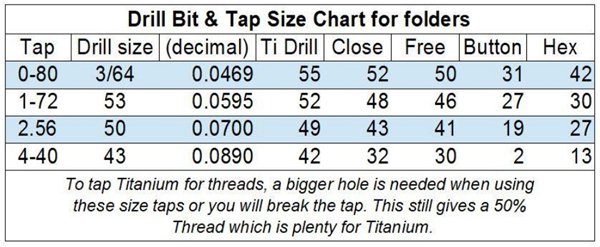

Choosing the Right Bits and Taps

Choose the appropriate bit that matches the material you want to machine. Expert machinists often recommend using high-speed steel to create threads in most metals.

In addition, ensure the tap radius corresponds with the preferred thread size to achieve a precise threaded blind hole. Depending on the blind hole depth, consider whether the type of tap, either a plug, taper, or bottoming tap, is the right fit for threading the blind hole.

Drill Depth Clearance

Measure and mark the desired depth on the drill bit to avoid drilling overly deep cavities because it weakens the material and increases the risk of material breakage. You can also control the drilling process using adjustable depth collars or depth stops on the drill press.

More importantly, consistently checking the depth clearance before drilling will help to prevent damage to the workpiece. Also, refer to design specifications to drill blind holes of the correct depth.

Hole Placement and Orientation

Hole placement and orientation influence the manufacturability and usefulness of parts significantly. To accurately drill blind holes, mark the holes’ locations with layout tools such as layout squares and center punches. As you create the blind holes, ensure their orientation matches the desired function of the final product or assembly, allowing smooth integration for designs.

Hole Diameter

The required hole diameter will determine the ideal drill bit size. The drill bit chart is a reliable reference for choosing a suitable drill bit size for the hole. Also, ensure to test the fit of the bit in scrap material before drilling the final blind hole.

Clean Blind Holes

Use the appropriate cutting fluid or lubricant to reduce heat buildup and friction during drilling. Use a cleaning brush or compressed air to extract debris from the blind hole. However, it is crucial to inspect the blind hole and confirm it is clean and clear before tapping it.

Blind Hole vs. Through Hole: What are the Differences?

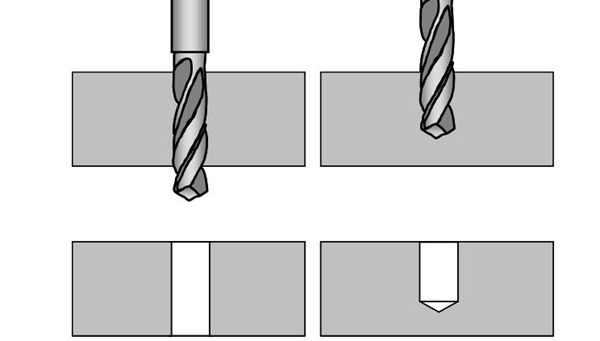

Besides their names, the differences between a blind hole vs. a through hole involve the process and the results. Blind holes do not break through the workpiece; they are only drilled to a specific depth that is a fraction of the total part’s thickness. A through hole or thru-hole is created to go through to the workpiece’s other side.

Machinists create blind holes in the workpiece to make recesses for fasteners. These blind holes often offer aesthetic benefits suitable for automotive, architecture, and consumer goods applications. Through holes are commonly used in assemblies where the components require secure fastening and alignment. However, a blind hole is a perfect choice in situations where you must avoid compromising the workpiece’s functionality or appearance on the opposite side.

In addition, the through holes are compatible with fasteners like bolts, screws, or pins that can completely pass through the material and secured with washers or nuts on the opposite side.

Other Types of Holes in Machining

Blind holes and through holes are the common types of holes used in product manufacturing. Other types of holes in manufacturing include:

Simple Hole

A simple hole is the most widely used hole in engineering and machining. It is usually straight, cylindrical, and has a constant diameter that extends through the material’s thickness. These holes are perfect for assembly, clearance, and location purposes.

Reamed Hole

A reamed hole is smoothened and sized to a precise diameter, with a preferred finish by a unique CNC tool known as a reamer.

Countersunk Hole

This is a conical type of hole created by drilling into a workpiece to ensure a bolt or screw head can flush with the material’s surface. Machinists cut a countersink in a workpiece to give it a flat surface and prevent the protrusion of a screw or bolt.

Counterbore

A counterbore is a flat-bottomed hole cut bigger and deeper than the existing hole in a workpiece material. It involves drilling a cylindrical recess into a material to make a flat surface around the hole. It has a larger diameter at the top, which accommodates the head of the bolt or screw.

Tapped Hole

A tapped hole is a hole with threads cut into it with a specialized tool known as a tap. The tapping process cuts threads into the workpiece material with the desired depth. Tapped holes apply to components like screws or bolts that require a secure fastening mechanism.

Tapered Hole

A tapered hole is another commonly used hole in engineering. It features a gradual diameter change from one end to the other. This hole is used in various applications, like press-fit joints, to hold two components firmly in an assembly.

WayKen’s Machining Capabilities for Different Holes and Complex Structures

WayKen offers comprehensive machining capabilities including complex geometry and various hole types. From prototypes to production, our CNC machining solutions ensure accuracy and consistency in every project. With advanced CNC technologies and a highly skilled team, we deliver to meet different machining requirements for industries such as aerospace, automotive, and medical. Contact WayKen for a new project and not let you be disappointed.

Conclusion

Blind holes are integral to the proper fit and function of different components with complex shapes. Machinists use this feature to support fasteners, improve surface aesthetics, and strengthen machined parts.

FAQs

What is a threaded blind hole?

A threaded blind hole is a type of hole with threads that don’t pass through a workpiece completely. The thread is cut inside the hole to facilitate a secure and reliable connection between mating parts.

What material can blind holes be machined?

Machinists create blind holes in different materials, such as plastics, metals, and composites. However, the material’s properties may determine the compatible machining methods and tools.

What are the standard measurement and inspection processes for blind holes?

Product engineers often employ different quality control methods to ensure accuracy in blind hole machining for reliable parts assembly. Metrology tools and inspection processes, surface profilers, non-destructive testing, and coordinate measurement machines are typical apparatuses that help achieve accurate outcomes in blind holes.